Grand Rapids and Indiana Railroad

By Fred Seibold ’53

Illustrations from Fred’s collection

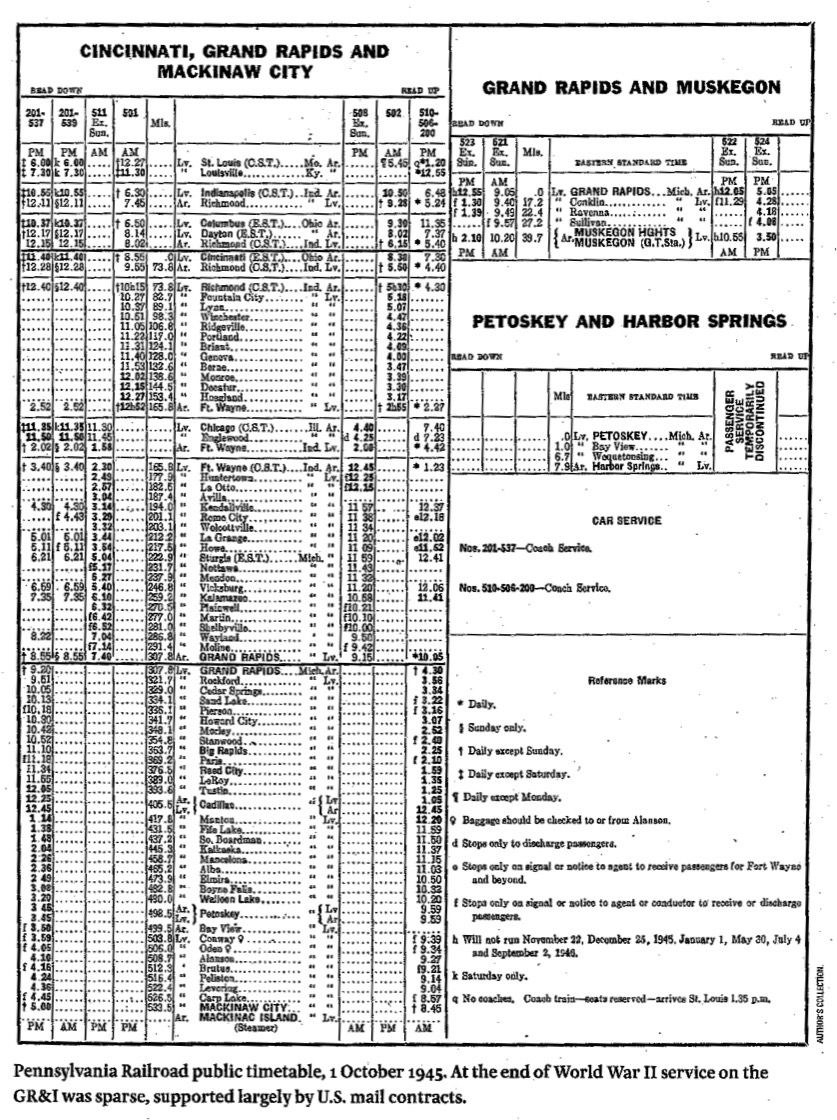

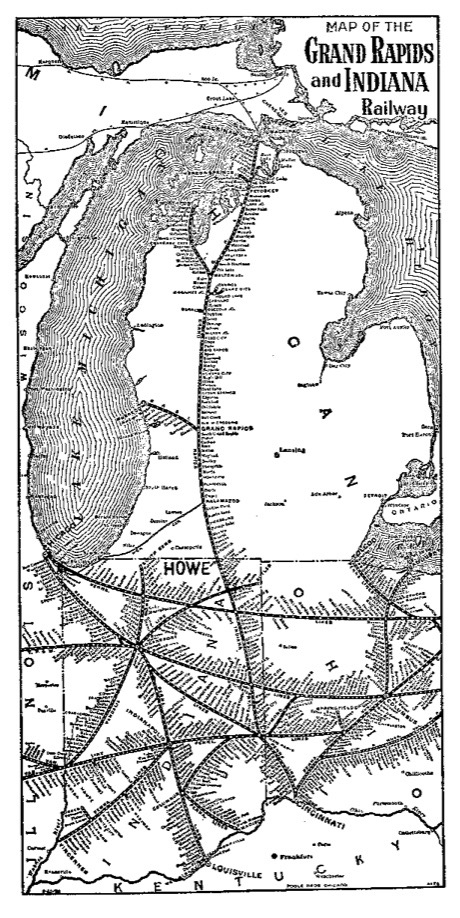

This map on the last page of the 1909 Howe School™ catalog caught my eye, lifelong rail buff that I am. On the lower border of the map appears “Poole Bros. Chicago” which tells me that this is an official railroad map. Like many which Poole Bros. made for railroad timetables and listings in the Official Guide, this was a 1000 page+ monthly magazine printed on newsprint containing all the timetables of the many hundreds of passenger trains running all over the country. The copies were distributed to the thousand or so railroad stations listed in the index of each issue. Back then, all the intercity mail was carried in “Mail Cars” on these passenger trains, to be sorted en route. You could go down to the Howe depot (below)…

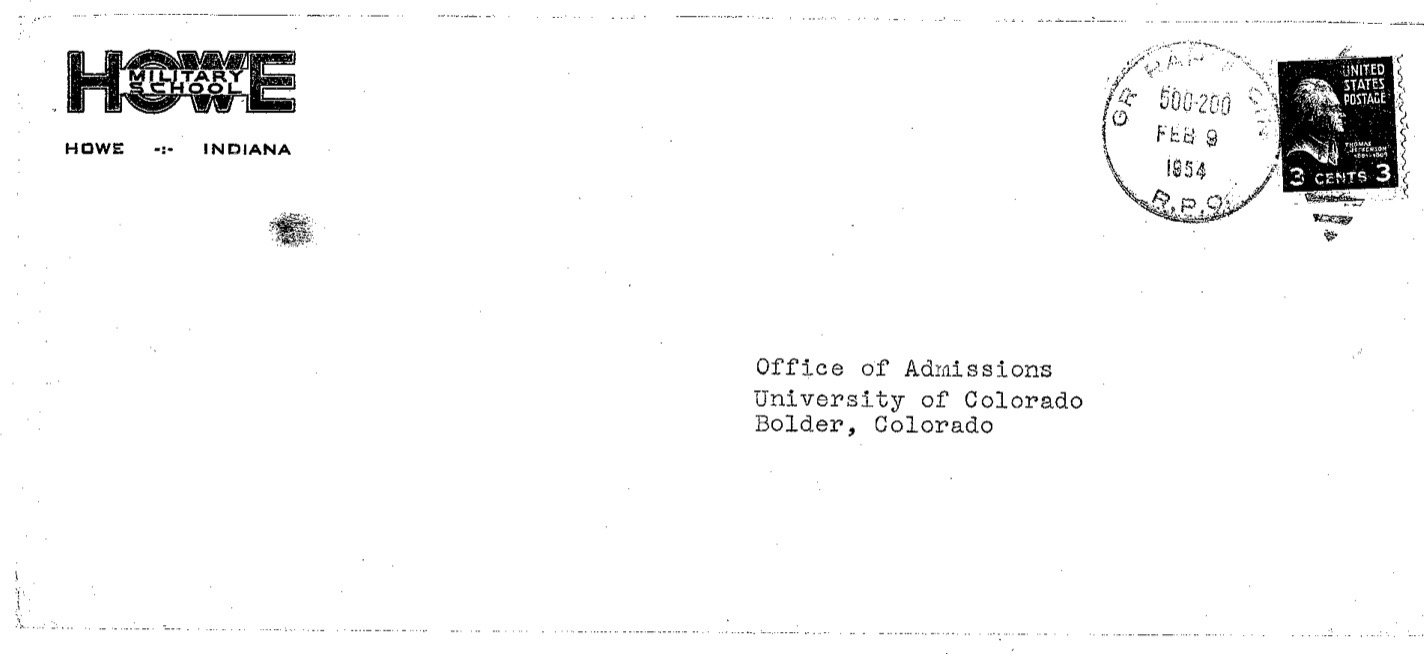

…and mail the letter into the letter slot on the side of the mail car. The Railway Post Office (RPO) cancellation shows that this letter (below) from HMS was mailed on trains 500 – 200 running from Grand Rapids to Cincinnati on February 9, 1954.

So why is this map in a Howe catalog?

Probably because some of the money that established Howe School™ was a result of John and James Howe investing in part of the GR&I. The earliest proposal for the GR&I started in 1855. Various promoters advanced countless proposals, but it took the railroad building boom of the 1870s before you could hear a Choo Choo in Lima (Howe). Notice the name changed to Howe on the map, coincidentally in 1909.

The impetus to build came from the Land Grant Act which gave railroad promoters alternate sections (a section = 640 acres) of land along the track AFTER the railroad was built. There were construction deadlines in the franchises, so a savvy GR&I promoter divided the proposal into several subsidiary companies, one of which was the Grand Rapids and Fort Wayne Railroad. Three of the 13 organizing directors of the Grand Rapids and Fort Wayne were from Lima (Howe): John Howe, James Howe, and Francis Jewett. We can assume it took a sizable investment to get three of the 13 seats on that board from one small unincorporated hamlet along the route.

Finally, with construction deadlines looming, friendly smiling Pennsylvania Railroad executives in Philadelphia offered to build and equip the railroad in return for the land grant lands. This information comes from Graydor M. Meints’ excellent history “The Fishing Line,” as the GR&I became known (ISBN 9781609175795, Michigan State University Press); he estimates that the Pennsylvania construction returned the eastern investors $3 million on a $200,000 investment. The GR&I was finally absorbed into the mighty Pennsy in 1920. It was abandoned in 1976 from Kalamazoo to Ft. Wayne. after the notorious Penn-Central bankruptcy. A stub remains today in Sturgis extending south to the state line, operated by the Michigan Southern short line.

Although the railroad depot housing the Sturgis Museum is next to the former GR&I track, it is not the GR&I depot. It is actually the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern (New York Central) Sturgis depot which was moved to this location by the museum.

The Howe investments would have been very profitable without the land-grant lands. The GR&I opened up vast timberlands in western Michigan to logging. The original idea for building the GR&I was to haul the lumber to Cincinnati and the Ohio River. As east-west railroads developed, the GR&I got many rail connections to the rest of the country. The tourist passenger business later boomed and was strong until “hard roads,” jet airliners, interstate highways, and the St. Lawrence Seaway came along. Three trains each way each day to Mackinaw are gone but not forgotten.

By the mid-20th Century, very few Howe cadets arrived in Howe by train. I tried to get my folks to let me, but they wouldn’t; too many transfers. My brother and I took Wabash Cannonball train (really) from central Illinois to Fort Wayne then bus to Howe.

Here is the GR&I timetable from 1945 as reproduced in Meints’ superb book, below: